In the intricate world of financial compliance, circular transactions and funnel accounts stand out as sophisticated methods employed by criminals to obscure the origins of illicit funds. Understanding these techniques is crucial for financial institutions striving to detect and prevent money laundering effectively. This guide delves into the methodologies of circular transactions and funnel accounts, highlights red flags for their identification, and provides actionable best practices for robust compliance.

To learn more, visit our full guide on BSA, AML, CFT, and OFAC regulations for financial services.

Why Financial Institutions Must Address Money Laundering Risks

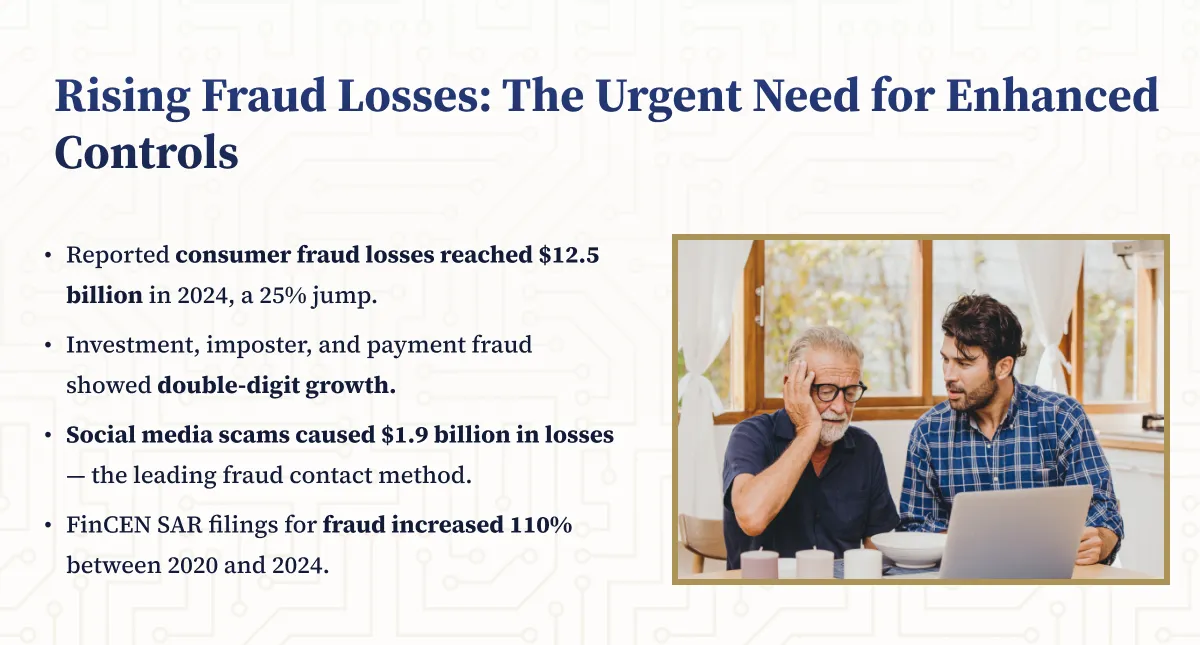

Money laundering poses a persistent threat to the global financial system, facilitating various criminal activities such as terrorism, drug trafficking, and corruption. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates that between 2% and 5% of global GDP, equating to $800 billion to $2 trillion, is laundered globally each year. Financial institutions play a pivotal role in combating this menace by implementing stringent Anti-Money Laundering (AML) regulations under the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). Central to these efforts are obligations to monitor, detect, and report suspicious activities. Non-compliance can lead to severe penalties, including substantial fines, sanctions, and reputational damage.

What are Funnel Accounts & Circular Transactions?

Funnel Accounts: Where Funds are Moved

Funnel accounts are specialized financial accounts designed to aggregate deposits from multiple locations into a central account. Typically facilitated by a network of "smurfs" (individuals conducting small deposits) the funnel account serves as a conduit for converting aggregated illicit funds into legitimate revenues. These accounts are often strategically placed near geographical boundaries, such as the U.S. southwest border, to facilitate swift and undetected movement of funds.

Circular Transactions: How Funds are Cycled

Circular transactions involve the repeated movement of funds through a series of accounts, often returning to the original account. This cycling of money obscures its origins and creates a convoluted trail that complicates detection efforts. Known also as round-tripping, circular transactions inflate revenue or business activity without any genuine exchange of value, making illicit funds appear legitimate.

Funnel Account Methodologies and Red Flags

Understanding the operational mechanics of funnel accounts and recognizing associated red flags is vital for financial institutions in detecting and preventing money laundering activities. Funnel accounts are a significant concern because they facilitate the movement of illicit funds under the guise of legitimate transactions.

How Funnel Accounts Are Used to Launder Money

The operation of funnel accounts involves a series of coordinated steps designed to move funds discreetly and efficiently. Here's a detailed breakdown:

1. Depositing Funds Through Structuring and Smurfing

Multiple individuals, called “smurfs”, deposit small amounts of money into the same funnel account from diverse geographic locations or financial institutions to avoid the $10,000 threshold triggering CTRs. Learn more in our detailed Structuring and Smurfing Guide.

2. Aggregation of Funds

The central funnel account consolidates these small deposits, amassing a substantial sum without raising immediate suspicion. Legitimate transactions may be mixed with illicit deposits to further obscure illegal activities.

3. Funding Further Activities

The aggregated funds are either withdrawn in bulk for integration into criminal operations or transferred to other accounts for further layering and processing. Funds can be wired domestically or internationally to co-conspirators for use or used to buy high-value assets like real estate, luxury goods, or vehicles.

4. Rapid Withdrawal or Transfer

Funds are quickly withdrawn or wired out of the funnel account, ensuring that the launderer maintains control and minimizes the risk of detection. Speed is critical in funnel account operations. Quickly moving funds minimizes the chance of detection by anti-money laundering systems that may flag unusual activity over time.

What is Trade-Based Money Laundering (TBML)?

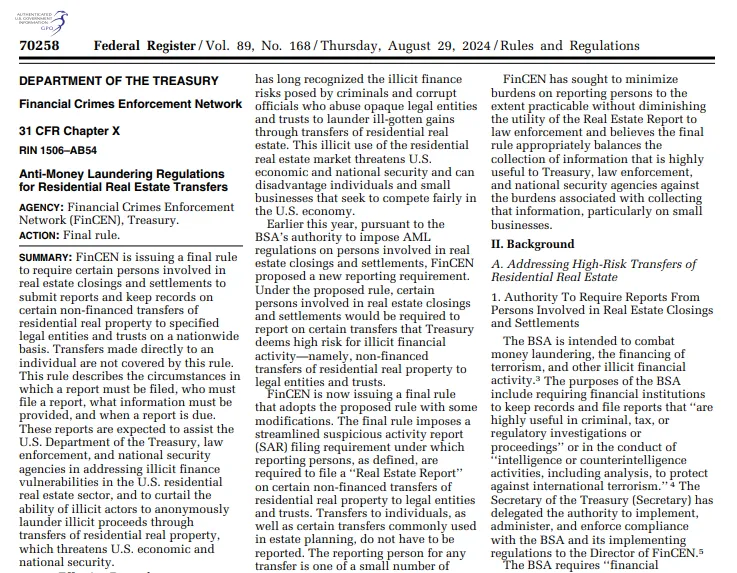

Trade-Based Money Laundering (TBML) is a method by which criminals use international trade transactions to disguise and move the proceeds of crime. TBML exploits the complexity of trade systems and the volume of international trade to obscure illicit financial flows.

%2520Process.webp)

Common Techniques in TBML:

- Over/Under-Invoicing: Misrepresenting the price of goods or services to transfer value between importer and exporter.

- Multiple Invoicing: Issuing more than one invoice for the same shipment to justify multiple payments.

- Falsifying Goods or Services: Misrepresenting the quality or quantity of goods.

- Phantom Shipments: Documenting shipments that never occur.

TBML and Funnel Accounts Connection

Funnel accounts can facilitate TBML by providing the means to collect and transfer funds required for trade transactions that are part of laundering schemes. Here's how the scheme unfolds, using the example of Mexican cartels:

Here’s how the scheme typically unfolds:

- Opening a Funnel Account: A colluding business or individual opens a funnel account in the U.S. or Mexico.

- Small Deposits: Cash is deposited in amounts below $10,000 by various individuals ("smurfs") to avoid triggering CTRs.

- Funding Purchases: The funds from the funnel account are used to wire money or issue checks for the purchase of goods, including high-value items or bulk commodities.

- Shipment of Goods: The purchased goods are shipped to the origin country (e.g., Mexico), where they are sold, generating legitimate revenue.

- Return of Proceeds: The proceeds from the sale are returned to the criminal organization in local currency, providing a "clean" source of funds that can be integrated into the financial system without arousing suspicion.

12 Red Flags to Identify Funnel Accounts

Detecting funnel accounts requires vigilance and the ability to recognize subtle indicators of suspicious activity. Key red flags include:

1. Multiple Deposits Followed by Quick Transfers to Other Accounts

A pattern of small deposits followed by rapid transfers or withdrawals suggests an attempt to consolidate and redistribute illicit funds.

2. High Aggregate Deposits with Low Account Balances

While individual deposits remain below reporting thresholds, the cumulative total may indicate significant illicit activity. Frequent withdrawals from the account ensure the balance remains low.

3. Deposits Made by Various Individuals or Companies

Involvement of multiple depositors from different entities can signal the use of funnel accounts for collective money laundering efforts.

4. Deposits Originating from Locations Outside the Account's Banking Area

Funds deposited from diverse geographic locations, especially those unrelated to the account holder’s business operations, raise suspicion.

5. Deposits from Diverse Sources (Cash, Checks, Wire Transfers, ATMs)

Varied payment methods used to distribute funds across different channels can indicate efforts to mask the origin and flow of money.

6. Accounts Opened by Individuals with Temporary Immigration Documents

Use of accounts by individuals with transient or non-permanent status may be a tactic to quickly move funds without establishing long-term ties.

7. Immediate Withdrawals or Wire Transfers Following Deposits

Quick movement of funds after deposits reduces the window for detection and increases the likelihood of obscuring the fund trail.

8. High Number of Charge-Backs

Frequent reversals of transactions can indicate attempts to complicate the accounting trail and obscure the original source of funds.

9. Financial Activity Not Aligned with the Depositor’s Stated Business or Occupation

Discrepancies between the account holder’s declared business activities and their financial transactions can signal illicit fund movement.

10. Anonymous Cash Deposits in One State with Rapid Withdrawals in Another

Geographic dissonance between deposit locations and withdrawal points can indicate deliberate attempts to obscure the money trail.

11. Sudden Changes in Account Activity Patterns

Unexpected shifts in transaction behavior, such as increased volume or frequency, may suggest laundering activities taking place.

12. Use of Branch Shopping to Obscure Fund Origins

Conducting transactions across multiple branches to distribute deposits helps minimize the risk of detection by spreading out suspicious activity.

%201%20(1).svg)

%201.svg)

THE GOLD STANDARD INCybersecurity and Regulatory Compliance

Circular Transaction Methodologies and Red Flags

Circular transactions manifest in several forms, each designed to manipulate financial records and disguise illegal activities. The primary types include accounting, trading and tax evasion round tripping.

Accounting Round Tripping

Accounting round-tripping involves recording transactions that lack genuine economic substance. Funds are moved between entities or accounts without any real business purpose, merely to distort financial statements. This practice can artificially inflate revenues, assets, or trading volumes, misleading investors, regulators, and other stakeholders.

How Account Round Tripping Works:

- Simulated Sales or Purchases: A company may "sell" assets to another entity with the prearranged agreement to buy them back at a similar price.

- Circular Fund Movement: Funds are transferred between related parties, ending up back at the original entity, giving the appearance of legitimate transactions.

- Financial Statement Manipulation: By recording these non-substantive transactions, companies can inflate revenue, mask losses, or meet performance targets.

Trading Round Tripping

Trading round-tripping involves executing trades that serve no economic purpose other than to create artificial trading volumes or manipulate market prices. These trades can involve financial instruments such as securities, commodities, or derivatives.

How Trading Round Tripping Works:

- Prearranged Trades: Two or more parties agree to buy and sell the same asset among themselves repeatedly.

- No Market Risk: Since the trades are prearranged, there's no real market exposure or risk to the parties involved.

- Volume Inflation: The repeated trades inflate trading volumes, potentially affecting market perceptions and prices.

Tax Evasion Schemes

Circular transactions are used to evade taxes by manipulating financial statements and transactions to reduce taxable income unlawfully. This often involves creating fictitious expenses or artificially lowering reported profits.

How Tax Evasion Schemes Work:

- Fake Loan Agreements: Entities simulate loans between related parties, allowing the "borrower" to deduct interest payments that don't actually occur.

- Inflated Expenses: Companies record expenses for services or goods that were never provided.

- Profit Shifting: Profits are shifted to jurisdictions with lower tax rates through artificial transactions.

5 Common Circular Transactions Methods

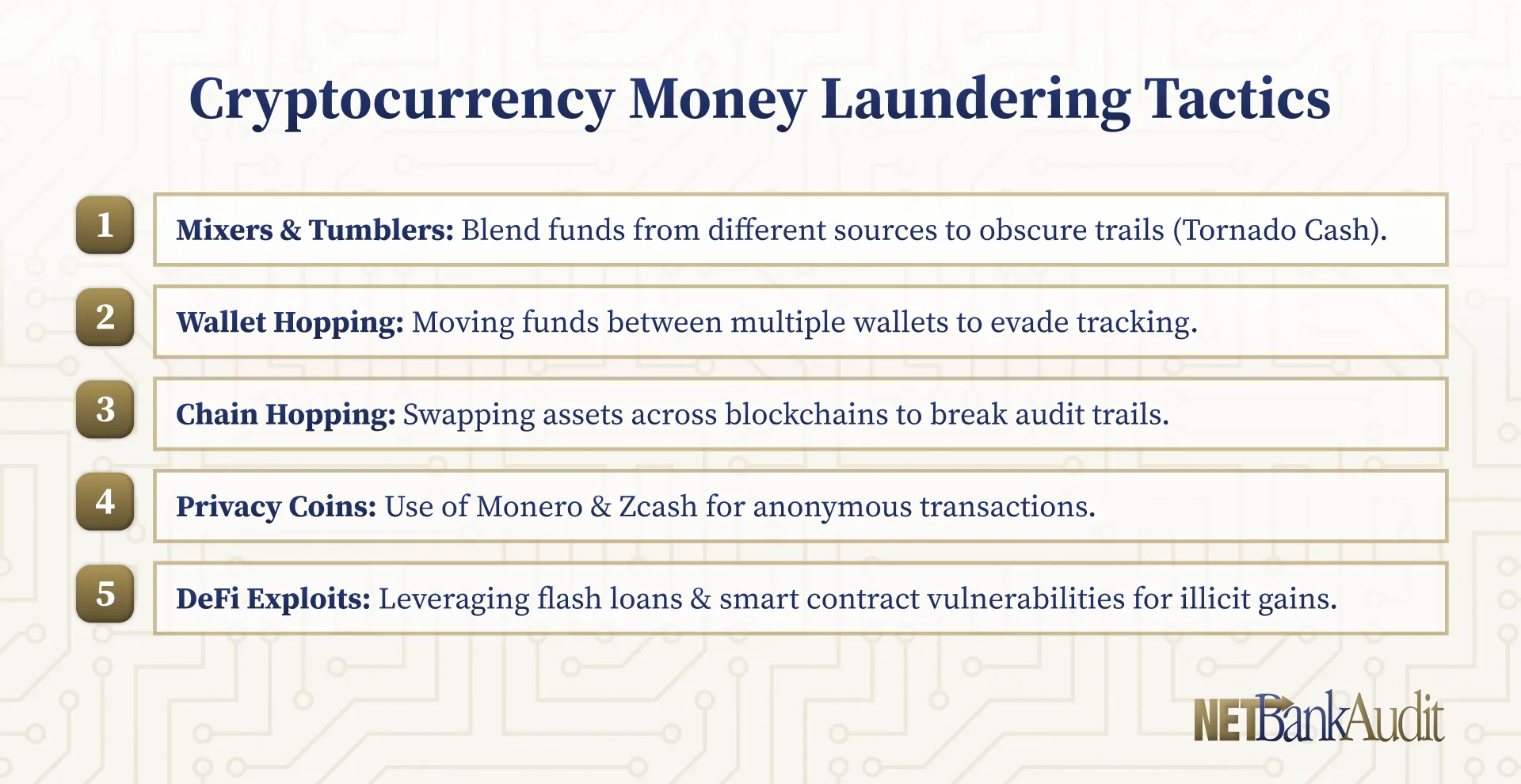

Money launderers employ various techniques to execute circular transactions, each designed to obscure the money trail and evade detection:

1. Shell Companies

Shell companies are entities without active business operations or significant assets, often registered in offshore financial centers with lax regulatory oversight. They exist primarily on paper, providing a legal front for illicit activities. Real owners hide behind layers of corporate structures, making it difficult to trace the source of funds. Transactions are conducted between shell companies to create the appearance of legitimate trade.

2. Asset Transfers

Transferring assets such as real estate or securities between entities at pre-agreed prices to create the illusion of legitimate transactions. Assets are bought and sold rapidly at inflated or deflated prices to transfer value without a clear money trail. Illicit funds are used to purchase assets, which are then sold, providing "clean" money from the sale.

3. Loan Agreements

Fake loan agreements between related parties are crafted to mimic legitimate financial transactions. In this, regular "interest" payments are made, providing a pretext for transferring funds. Complicated loan structures make it difficult for authorities to unravel the true nature of transactions. Loans may be forgiven without proper documentation, effectively transferring wealth.

4. Trade-Based Techniques

Trade-Based Money Laundering (TBML) involves manipulating trade transactions to obscure the movement of funds. This can include over-invoicing, under-invoicing, multiple invoicing, or falsely described goods and services.

5. Company Reinvestment

Illicit funds are invested into legitimate businesses or reinvested into new ventures. This blending of dirty money with legitimate revenue makes detection more challenging. This method effectively integrates dirty money into the legitimate economy, causing market distortion.

7 Red Flags to Identify Circular Transactions

Recognizing red flags associated with circular transactions enables financial institutions to implement effective monitoring and reporting mechanisms.

Key red flags include:

1. Repeated or Cyclical Transactions with the Same Counterparty

Frequent fund transfers between the same parties without a valid business reason can indicate restructuring attempts to obscure the true fund origin.

2. High Transaction Volume Relative to the Nature of the Account

Significant increases in transaction volumes that do not align with the account’s typical activity level suggest potential laundering activities.

3. Use of Accounts with Minimal or No Declared Business Activity

Accounts associated with little to no legitimate business operations may be used primarily for launderers to cycle funds.

4. Unusually Consistent Revenue Growth

Companies displaying steady revenue growth without a corresponding increase in business activities or market presence may be engaging in circular transactions.

5. High Sales Volume with Negligible Change in Receivables

Discrepancies between sales figures and receivables can indicate manipulative accounting practices aimed at masking money laundering.

6. Significant Increase in Sales Near Reporting Periods

Sudden spikes in sales close to the end of reporting periods may be orchestrated to manipulate financial statements and obscure illicit activities.

7. Falsified Invoices or Fictitious Loans

Creation of fake invoices or loan agreements to justify inconsistent financial transactions is a common tactic in circular laundering schemes.

6 Real World Examples of Money Laundering Using Circular Transactions & Funnel Accounts

Understanding real-world applications of circular transactions and funnel accounts provides invaluable insights into how these techniques are employed and the severe repercussions for those involved. Here are seven notable cases:

1. United States v. Greg Lindberg (2024)

Greg Lindberg, a Florida businessman, pleaded guilty to conspiracy charges involving a $2 billion fraud and money laundering scheme. From 2016 to 2019, he orchestrated circular transactions among a network of companies, diverting funds from insurance companies he controlled to his affiliated entities, concealing the true financial condition of his companies, and using the misappropriated funds for personal benefit. This included forgiving over $125 million in personal loans. This intricate web of transactions misled regulators and policyholders, enabling the movement of substantial illicit funds undetected.

2. United States v. Da Ying Sze (2021)

Da Ying Sze admitted to orchestrating a $653 million narcotics money laundering conspiracy. Sze utilized numerous bank accounts, often under names of other individuals, to deposit large sums of cash—sometimes exceeding $1 million in a single day. He bribed bank employees with over $57,000 in gift cards to facilitate these transactions and evade detection. A significant portion of the laundered funds—over $470 million—was processed through TD Bank.

3. United States v. Leonardo Ayala (2024)

Leonardo Ayala, a former TD Bank employee, was charged with facilitating money laundering activities in Colombia. Leonardo Ayala exploited his position at TD Bank to assist a sophisticated money laundering network. Working with a fellow bank employee who opened accounts under the names of shell companies and nominee owners, Ayala issued dozens of debit cards linked to these fraudulent accounts. These accounts were subsequently used to launder narcotics proceeds through cash withdrawals at ATMs in Colombia, facilitating the transfer of millions of dollars. In exchange for his role in the scheme, Ayala accepted bribes, further enabling the illicit activities.

4. United States v. Mark Grelle (2023)

Glenn E. Diaz, a former assistant district attorney, along with Peter J. Jenevein and Mark S. Grelle, was convicted of defrauding First NBC Bank out of over $550,000 through a scheme involving fake invoices and money laundering. Between April and December 2016, Diaz used fraudulent invoices for non-existent improvements to a Florida warehouse to secure overdrafts, which he funneled back into his personal accounts for luxury expenditures.

Jenevein and Grelle facilitated the scheme by creating false documents and conducting 17 round-trip transactions to conceal the fraud. The defendants face up to 30 years in prison for each bank fraud charge and 20 years for money laundering conspiracy, with sentencing set for July 2023. The case highlights significant abuse of trust and financial manipulation within the banking system.

5. United States v. Rajen Maniar (2021)

Rajen Maniar pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit money laundering. He was involved in circular transactions that moved funds through various accounts to obscure their illicit origins, exemplifying classic money laundering techniques. Maniar cooperated with federal authorities leading to a reduced prison sentence of one month, however he was ordered to pay over $26 million in restitution.

6. United States v. Peter McVey (2024)

Peter McVey, a former bank executive, pled guilty to violating the Bank Secrecy Act by aiding and abetting the willful failure to implement a proper anti-money laundering (AML) program at his bank.

Under pressure from management to rapidly grow assets, McVey played a central role in onboarding these high-risk customers and enabling their use of funnel accounts in "rent-a-tribe" schemes to evade usury laws and deceptive sweepstakes businesses linked to criminal organizations.

McVey currently faces a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison for his approval of agreements with forged signatures, failure to file required suspicious activity reports, and attempt to exempt the bank from CTRs.

Strengthen Your AML Program with NETBankAudit

Effectively addressing circular transactions and funnel accounts is essential for financial institutions to protect their operations, comply with regulatory standards, and uphold the integrity of the financial system. Robust compliance programs that include advanced monitoring systems, enhanced due diligence, employee training, and collaboration with industry leaders are vital in mitigating money laundering risks.

NETBankAudit is a trusted authority in identifying and combating sophisticated laundering techniques such as circular transactions and funnel accounts. With over two decades of experience in BSA, AML, and OFAC compliance, NETBankAudit offers tailored solutions designed to strengthen your institution’s defenses. Their team of seasoned professionals employs cutting-edge methodologies to perform risk assessments, audits, and compliance reviews, ensuring your organization meets the highest regulatory standards.

Whether you need expert guidance in detecting money laundering schemes, refining your compliance program, or implementing advanced detection tools, NETBankAudit is your partner in achieving operational excellence and regulatory adherence. Discover how NETBankAudit can safeguard your institution , and take the next step in fortifying your compliance program today.

For further resources and detailed guidelines, please refer to:

.avif)

.svg)

.webp)

.webp)

.png)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

%201.webp)

.webp)

%20(3).webp)

.webp)

%20Works.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

%20(1).webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

%201.svg)